Medical Informatics: An Introduction

I.MEDICAL INFORMATICS DEFINED:

For the last decade, the term medical informatics has increasingly been used to describe a broad range of intertwined disciplines. Unfortunately, this has led to some confusion regarding the ‘defini-tion’ of medical informatics. Many in healthcare use the term to describe all of medical computing and any related disciplines. However, the field of medical informatics is actually over thirty years in the making and focuses on the structure and effects of medical information rather than the electronic scaffolding necessary to shuttle the electrons to and fro.

The origins of the general discipline of “informatics” have been traced to a Russian publication entitled Oznovy Informatiki (Foundations of Informatics) published in 1968. It was then that the concept of information science was described within the context of an emerging computer age. The 1976 Oxford English Dictionary describes informatics as “the discipline of science which investi-gates the structure and properties of scientific information” (Collen,1996). Thus, strictly speaking, medical informatics is the discipline which investigates the structure and properties of medical information. In keeping with this view, Shortliffe and Perrault describe medical informatics in the following manner:

“..the rapidly advancing scientific field that deals with the storage, retrieval, and optimal use of biomedical information, data, and knowledge for problem solving and decision making.” (Shortliffe and Perrault,1990)

Most notably, this definition makes no mention of computers or information technology itself. Instead, it focuses on the subject matter—information, rather than the tool—a computer.

Medical informatics is about information and how it is captured, used, and stored rather than the equipment that makes it all possible. The distinction is not always obvious. However, understanding the meaning, relationships and properties of information is as important to medical computing as the hardware conduit necessary for its distribution. This is vital to understanding the field of medical informatics and how it will impact medical computing in the future.

II. THE ORIGINS OF MEDICAL INFORMATICS

The discipline known as medical informatics was presumably born when first described in the document Education in Informatics of Health Personnel (1974). Although this is the earliest this discipline was given a name, examples of informatics principles date much earlier.

A Scottish surgeon devised a novel method of representing knowledge based on the principle that all things are merely “concepts” which could then be described by terms. Two terms that de-scribed the same concept were called synonyms. He developed the thesaurus as a system to address the problem encountered when individuals describe the same concept with different terminology. Dr. Roget expanded the boundaries of knowledge representation when he published the Roget’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases in 1852.

Interestingly, Roget’s original methodology was again employed by the National Library of Medicine in 1986 when it began development of the Unified Medical Language Systems (UMLS) Metathesaurus. The UMLS Metathesaurus is a medical component of a large vocabulary system developed by the National Library of Medicine to address the need for a standardized medical vocabulary. Such a vocabulary is necessary for categorizing biomedical information sources in order to enhance information retrieval. Although the UMLS was initially developed to enhance biomedical information retrieval, it has also gained popularity as a vocabulary for computerized medical systems. At present, the UMLS Metathesaurus is a massive undertaking encompassing 500,000 terms and 252,000 concepts. The use of Roget’s thesaurus concept provided an easily scalable system that addresses differences in concept descriptions often encountered in medicine (NLM,1997).

Specific methods of information storage and data manipulation were employed as early as the turn of the century by Dr.John Shaw Billings, the Surgeon General of the Army and founding editor of the Index Medicus. In 1890, Dr. Billings was charged with tabulating the U.S. census and conceptualized what some consider the genesis of the information revolution. He described an electromechanical device that would tabulate the census automatically through the use of punch cards. The job of making this concept a reality fell to Herman Hollerith, a government statistician.

Fifty-six Hollerith machines were used to process census information for 62 million people in 1890. This was done 2 years ahead of schedule and $5 million under budget! Hollerith left his government job in 1896 to establish International Tabulating Machines which became International Business Machines(IBM) in 1924 (Collen,1986).

Figure 1: Dr.John Shaw Billings

Dr.Billings also established and became the first director of the National

Library of Medicine (NLM). The first stacks of the library contained

Dr.Billings’ personal medical library which he donated. Dr. Billings’ work intersected technology again in 1966 with the computerization of the Index Medicus. The resulting system known as MED-LARS became the first such publicly accessible online information system. Today, such systems are taken for granted as they are weaved into every aspect of our lives

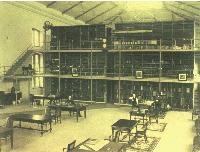

Figure 2: The National Library of Medicine (c.1887)

III. MEDICAL INFORMATICS COMES OF AGE

Since the formalization of the discipline in 1974 through the early 1990’s, medical informatics became increasingly recog-nized as an important component of the overall practice of medicine(Collen,1996). Many medical informatics academic research centers developed computerized medical records systems incorporating medical informatics design principles. Most of these survive today and are making a resurgence

given the shift to clinician driven designs. An example of such a system is the HELP system devel-oped by the University of Utah and deployed within the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City. Other examples of medical informatics groups developing entire medical computing systems include TMR (The Medical Record) at Duke University and The Regestrief Medical Record System at the Univer-sity of Indiana. The Regenstrief system today contains over 1.5 million patient encounters in digital format and is one of the most extensive repository of medical record information in the world (MacDonald, 1997).

Fig 3. Medline

This period of time also saw the emergence of medical informatics programs in the United States and the emer-gence of the National Library of Medicine as a staunch supporter of the discipline. In 1986, Dr. Don Lindberg became the director of the NLM and ushered in a new era.

A pathologist by training, Dr.Lindberg has led the NLM through major accomplishments including the further refinement of MEDLINE, the establishment of the Visible Human graphical datasets, the development of the Unified Medical Language System, and the funding of dozens of Internet con-nections to rural hospitals. Under his direction, The National Library of Medicine continues to be the major supporter of academic research in the area of medical informatics.

IV. THE FUTURE OF MEDICAL INFORMATICS

Even though the area of medical computing has contributed significantly to improvements in healthcare, there are still tremendous challenges for future medical informaticians to address. For example, it is often assumed that benefits of a paperless record will immediately realized once all the information already available on paper is digitized. A study by Shortliffe casts a shadow on this optimism. His study of 168 consecutive visits to an Internal Medicine clinic revealed that despite having the complete medical chart and all laboratory and radiology reports (those with missing charts and reports were excluded from the study), in 81% of the visits some information deemed important by the physician was not available. In other words, this information had not been captured in the process of generating all the standard medical record information we deem necessary today. This is a problem which is unlikely to be solved by digitizing the paper-based information resources already available to physicians. It is an information problem, not a computer problem.

Similar findings come from the Workgroup for Electronic Data Interchange. WEDI reported that 50% of paper-based medical records today are either missing completely or contain incomplete data(WEDI, 1996). Another study conducted by the Institute of Medicine reported that 30% of treatment orders are not documented at all (IOM, 1996). These are problems of information acqui-sition and require an intimate knowledge of the information content, the environment in which it is collected, and the technology being used to capture it in order to undertake a viable solution. These are the tools of a successful medical informaticician.

In summary, the field of medical informatics is not new, yet seems to only be in its infancy in terms of enhancing medical practice. Medical informatics has the potential of benefiting patient care as much as a newly discovered drug or therapy, yet the direct benefits will not come in the classic form—therapeutic interventions. Instead, they will be derived from enhancing our ability to care for patients through the improved delivery of medical knowledge and information. This is the promise of medical informatics and will be evident as medical practice forges ahead in the information age.

*Photographs courtesy of the National Library of Medicine (http://www.nlm.nih.gov)*

FURTHER READING:

A History of Medical Informatics in the United States: 1950-1990 (Collen, AMIA Press 1996)

Information Retrieval: A Health Care Perspective (Hersch, Springer-Verlag, 1996)

Medical Informatics : Computer Applications in Health Care (Shortliffe, Addison Wesley, 1990).

Collen MF. Origins of Medical Informatics. West J Med. 1986 Dec; 145:778-785.

Lindberg DA. The National Library of Medicine and Medical Informatics. West J Med 1986 Dec ;145:786-790.Altman RB. Informatics in the Care of Patients: Ten Notable Challenges. West J Med 1997 Feb.